Caziel (b. Kazimierz Józef Zielenkiewicz, June 16, 1906, Sosnowiec, Poland—d. 1988, England) was a significant figure in 20th-century modern art. His journey from figurative to abstract art is emblematic of the broader shifts in European modernism, particularly within the vibrant artistic milieu of post-war Paris. Caziel’s artistic evolution was profoundly shaped by his relationships with key figures of the École de Paris, including Pablo Picasso, and his interactions with influential artists and intellectuals such as the renowned art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. The impact of World War II on his life and art was also a defining element in his career, driving his shift towards abstraction and influencing his later works.

Caziel was born into a family that endured considerable hardship following the early death of his father. Despite these challenges, his mother ensured that Caziel received a strong education. From an early age, he showed an aptitude for art, which led him to pursue formal training. In 1927, he began his studies at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, where he was mentored by Tadeusz Pruszkowski, a leading figure in Polish art known for his emphasis on both technical skill and imaginative exploration.

At the Academy, Caziel was exposed to the French Post-Impressionist movement, which was highly influential among the students and faculty. The works of Paul Gauguin, Paul Cézanne, and Henri Matisse were particularly revered, and their influence is evident in Caziel’s early development as a painter. His paintings from this period often exhibit a Cézannesque approach to technique and color, with a strong emphasis on structure and form. Additionally, his designs for the ballet, which were inspired by Matisse’s "La Danse" (1910), reflect his engagement with Fauvism’s bold use of color and dynamic compositions.

However, Caziel’s artistic identity was not solely defined by these French influences. He also drew deeply from his Polish heritage, incorporating elements of Polish folklore into his work. This blend of Post-Impressionist techniques with traditional Polish motifs created a unique visual language that set Caziel apart from his contemporaries. His works from this period demonstrate a profound understanding of color and composition, as well as a deep respect for the cultural traditions of his homeland.

Caziel’s aspirations to immerse himself in the Parisian art scene were realized in 1937 when he won the prestigious Piłsudski Bursary, a Polish national scholarship awarded to support artistic study abroad. This move marked the beginning of a significant chapter in his artistic career. Paris, at the time, was the epicenter of the art world, attracting artists from across the globe who were eager to engage with the latest developments in modernism. For Caziel, the city offered the opportunity to study the works of the great masters firsthand and to interact with some of the leading figures of the day.

In 1938, Caziel received a commission to decorate the Pop Iwan Observatory in the Carpathian Mountains. Once the highest inhabited structure in Poland, the observatory fell into ruin following the Second World War. This project was the last time Caziel returned to Poland; France became his home.

His time in Paris was further extended in 1939 when Edouard Vuillard, an influential French painter and a key member of the Nabis group, intervened with the Polish authorities to grant Caziel permission to stay. However, the outbreak of World War II dramatically altered his circumstances. When Germany declared war on Poland in September 1939, Caziel, like many of his compatriots, felt compelled to take action. He voluntarily joined the Polish army in France, demonstrating his deep sense of duty and patriotism.

The war years were a period of intense upheaval for Caziel. The fall of France in 1940 and the subsequent Franco-German Armistice led to the disbandment of the Polish army, leaving Caziel and his comrades without a clear path forward. Fearing for their safety, Caziel and his Jewish wife, the painter Lutka Pink, fled to the south of France, where they were welcomed by the poet Blaise Cendrars in Aix-en-Provence. This period of exile was both challenging and transformative for Caziel. Separated from the cultural life of Paris and the safety of his homeland, he turned to the works of Paul Cézanne, who had also spent much of his life in Aix, for inspiration and solace.

During his time in Aix, Caziel studied Cézanne’s work in depth, creating a series of paintings that paid homage to the great modern master. These works, which included a series of nudes and landscapes, are characterized by strong contour lines, unusual compositions, and a restrained palette that reflects Cézanne’s influence. Notably, Caziel also painted a series of small oils depicting Mont Sainte-Victoire, one of Cézanne’s most iconic subjects. Through these works, Caziel sought to connect with the artistic legacy of Cézanne while also forging his path as a modern artist.

In Aix, Caziel also met the architect Le Corbusier, with whom he exchanged ideas about the integration of painting and architecture. This dialogue had a lasting impact on Caziel’s approach to art, particularly his interest in the relationship between form and space. Le Corbusier’s emphasis on proportion and his vision of a new architecture for the modern age resonated with Caziel, who had already demonstrated a keen understanding of these principles in his earlier frescoes in Poland. Upon his return to Paris in 1946, Caziel was commissioned to design the Polish pavilion for the UNESCO International Exhibition of Modern Art, a project that allowed him to apply these ideas on an international stage.

After the war, Caziel chose to remain in Paris rather than return to Poland, partly to protect Lutka from the trauma of returning to a country where her relatives had been murdered in Auschwitz, but also as he disagreed with returning to Poland under communist rule with the restrictions he would face. Life in post-war Paris was difficult, with resources scarce and the city struggling to recover from the occupation. However, the artistic community was vibrant, and Caziel was energized by the search for new forms of expression that characterized the post-war period.

Caziel’s career began to gather momentum during this time as he participated in several significant exhibitions. His first solo exhibition took place at the Galerie Allard in 1947, a prestigious venue that showcased the work of emerging modern artists. The exhibition was well received, and the inclusion of a monograph by the influential art critic Gaston Diehl in the catalogue further cemented Caziel’s growing reputation as a promising young artist. Shortly after, he was invited to exhibit for several consecutive years at the Salon de Mai, a key event in the Parisian art calendar that featured works by leading figures such as Picasso, Hans Hartung, Victor Vasarely and Alfred Manessier.

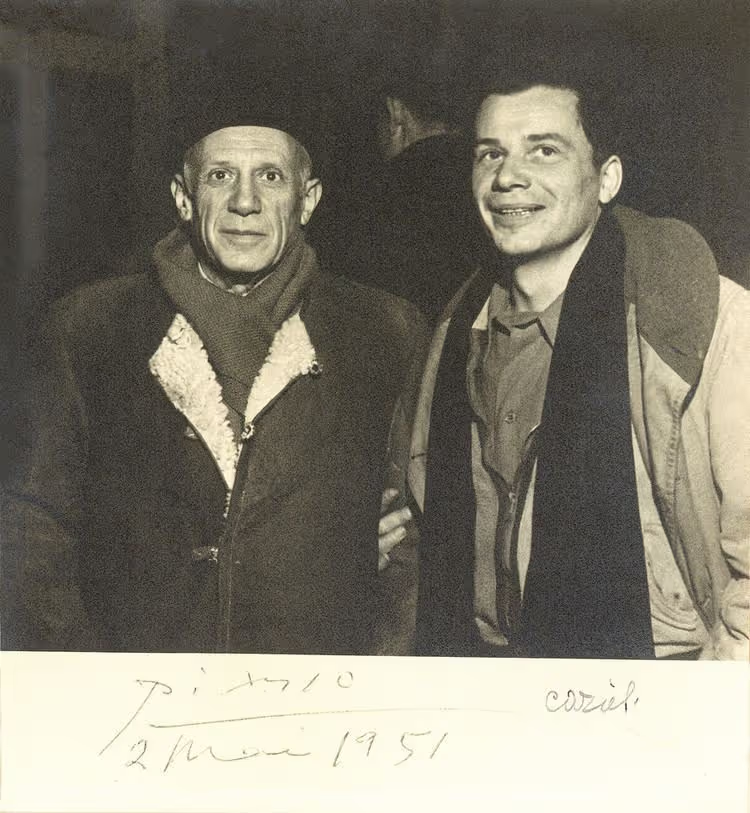

Caziel's friendship with Picasso deepened during this period, particularly from 1948 to 1952. The two artists bonded over their shared love of Polish folk art and their experiences as immigrants who could not return to their homelands. Picasso’s influence on Caziel was profound, particularly in the late 1940s when Caziel’s work often reflected a blend of lyrical and expressive compositions reminiscent of Picasso’s style. However, Caziel was also exploring new directions in his art, and by 1951, he had largely abandoned figuration in favor of abstraction.

In 1951, Caziel joined the "Groupe Espace," a collective that sought to unite Constructivist art with architecture to create a new environment suited to the modern age. This period marked a significant shift in Caziel’s work as he began to focus on the possibilities of geometric abstraction. His paintings from this time are characterized by rigorous compositional structures and a refined use of color, reflecting his deep engagement with the principles of Constructivism and his desire to push the boundaries of modern art.

In April 1952, Caziel met the young Scottish painter Catherine Sinclair during her exhibition at the Galerie Jeanne Castel in Paris. It was love at first sight, a powerful connection that neither could ignore. At the time, Caziel was still officially married to Lutka Pink, and he initially tried to suppress the feelings of intimacy and passion that had blossomed between him and Catherine. However, Lutka’s departure for America a month later and her tacit consent to Catherine moving into Caziel’s studio on avenue de Saxe marked the beginning of a profound emotional and creative partnership.

The couple’s presence at 59 avenue de Saxe, a hub for Poland’s artistic elite, was both exciting and challenging. The studio was hot in summer, cold and drafty in winter, and lacked general comforts. During a romantic camping holiday in the South of France, they decided that a home in the country would better suit their needs. They found their rural paradise in Ponthévrard, located on the southwestern outskirts of Paris. This idyllic setting became the backdrop for their secret love affair, as Catherine juggled her relationship with Caziel and her obligations to her family.

Catherine Sinclair, the headstrong artistic daughter of Sir Archibald Sinclair, Liberal Leader and Secretary of State for Air during World War II, was not expected to fall in love with a penniless artist. She was impeccably educated and possessed the social graces of her aristocratic upbringing. Yet, she was deeply in love with Caziel and willing to live a double life to maintain their relationship. For four long years, Catherine spent her winters in Scotland and England as the dutiful daughter, writing countless letters to Caziel in Paris. During the summers, they reunited, often with the help of Catherine’s former governess, who provided an alibi and a postal address in Paris.

Catherine’s love revitalized Caziel’s creativity. Though he had committed himself to abstraction, his passion for Catherine inspired him to temporarily return to a more immediate figurative style. He produced a series of large black ink and wash drawings, depicting figures in wild embrace, reminiscent of erotic scenes in Greek mythology. These drawings, which embodied archetypal projections of ecstasy, pain, solitude, and respect, appealed to the collective consciousness of what it means to be passionately in love.

Caziel found it difficult to work when Catherine was not by his side. She became his muse, inspiring a depth of emotion that he had never before experienced. In a letter from the autumn of 1952, Caziel wrote, “I shouldn’t be in love so much. It’s not good for me. Come as soon as possible. It’s impossible to live without you.” His letters from that period often ended with, “I kiss you on the mouth, your feet, your heart, and your eyes.” An avid reader of Greek classics, Caziel compared their love story to that of Ulysses and Penelope, albeit with reversed roles. He often referred to himself as Penelope, sewing and unpicking his canvases while waiting for his Ulysses-Katy to return.

By 1953, Caziel had reconnected with abstraction, continuing his exploration of geometric forms and compositional structures. In 1955, Catherine announced her love for Caziel to her parents, who, to her surprise, received the news with delight. Following his official divorce from Lutka in November 1956, Caziel and Catherine were married in Paris in June 1957, with Picasso’s close friend, Jaime Sabartés, as a witness. A year later, their daughter Clementina was born.

The couple spent twelve years in Ponthévrard before moving to Somerset, England, where they remained until their respective deaths in 1988 and 2004. Catherine Sinclair was not only Caziel’s beloved wife but also a talented painter in her own right. Her love and support were instrumental in revitalizing Caziel’s creativity and guiding his artistic evolution during their life together.

After moving to Britain, Caziel continued to develop his abstract style, producing works that were characterized by their clarity of form and intensity of color. His paintings from this period reflect a deep engagement with the possibilities of abstraction and a commitment to pushing the boundaries of modern art. In 1975, Caziel was naturalized as a British citizen, marking the beginning of a new chapter in his life.

Caziel’s later years were marked by continued artistic production and recognition. His work was featured in several significant exhibitions, including a major retrospective hosted by the National Museum in Warsaw in 1998, a decade after his death. This retrospective was a fitting tribute to an artist whose work had been deeply influenced by his Polish heritage, even as he made his mark on the broader European art scene.

Whitford Fine Art, which has represented the Caziel Estate since 1994, also played a crucial role in preserving and promoting his legacy. Since 1995, the gallery has held regular exhibitions, showcasing the full range of Caziel’s work from his early figurative paintings to his later abstract compositions. These exhibitions have helped to reintroduce Caziel’s work to a new generation.

Over the years, Caziel's works have been included in numerous solo and group exhibitions across Europe. Notable solo exhibitions include "Caziel: Abstraction Explored, Works from the Fifties" at Whitford Fine Art, London (2017), "Caziel: Espace - Abstraction" at Francis Maere Fine Arts, Ghent, Belgium (2014), and "Centenary Retrospective Exhibition" at Whitford Fine Art, London (2006). His group exhibitions include participation in "A Century of Polish Artists in Britain" at Ben Uri Gallery, London (2017), and regular exhibitions at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, during the 1960s.

Caziel’s works are part of important public collections, including the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris, the National Museum in Warsaw, the Łodz Museum of Art, and the Vatican Museum in Rome. His contributions to modern art have been documented in several key publications, including "Caziel 1906-1988, Catalogue Raisonné" by Dorota Monkiewicz (National Museum, Warsaw, 1998), and "The Grand Play of Light: The Art & Life of Caziel" by Jenny Pery (London, 1997).

Caziel’s legacy is preserved through numerous exhibitions and collections across Europe. His work is celebrated for its technical precision, emotional depth, and its synthesis of Polish artistic traditions with the avant-garde innovations of the École de Paris. His life and career encapsulate the dynamic intersections of influence and creativity that defined his era, marking him as a vital figure in the history of 20th-century modern art.

Caziel’s contributions to modern art remain a vital part of the cultural heritage of the 20th century. His work continues to resonate with audiences today, offering a unique perspective on the complexities of modern life and the enduring power of abstract art. His journey from the figurative traditions of his early years in Poland to the abstract innovations he pursued in France and England reflects the broader evolution of modern art, and his legacy endures as a testament to the transformative power of creativity.